Moving Beyond Language

In 1981, I was part of a small group of women who founded what was to become an ongoing Jewish feminist spirituality collective, B’not Esh (Daughters of Fire). The invitation letter to the first retreat described attention to God and God-language as a central purpose of our meeting. It spoke of “the shared longing…for a Judaism—and a Jewish community—which reflects and informs our sense of ourselves as heirs to and shapers of a tradition that celebrates both human and divine femaleness, and encourages exploration of the implications of such cosmic re/visioning for our relationships to one another, and our relationship to God.”

The letter was not modest in laying out our hopes for the weekend; it compared feminism’s challenge to Judaism to the challenge confronting the rabbis trying to reconstitute Judaism in the generation after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. But the letter also made clear that the outcome of the meeting would depend on the contributions of the participants; the organizers would provide only an outline of the retreat that would take on flesh in the course of our time together.

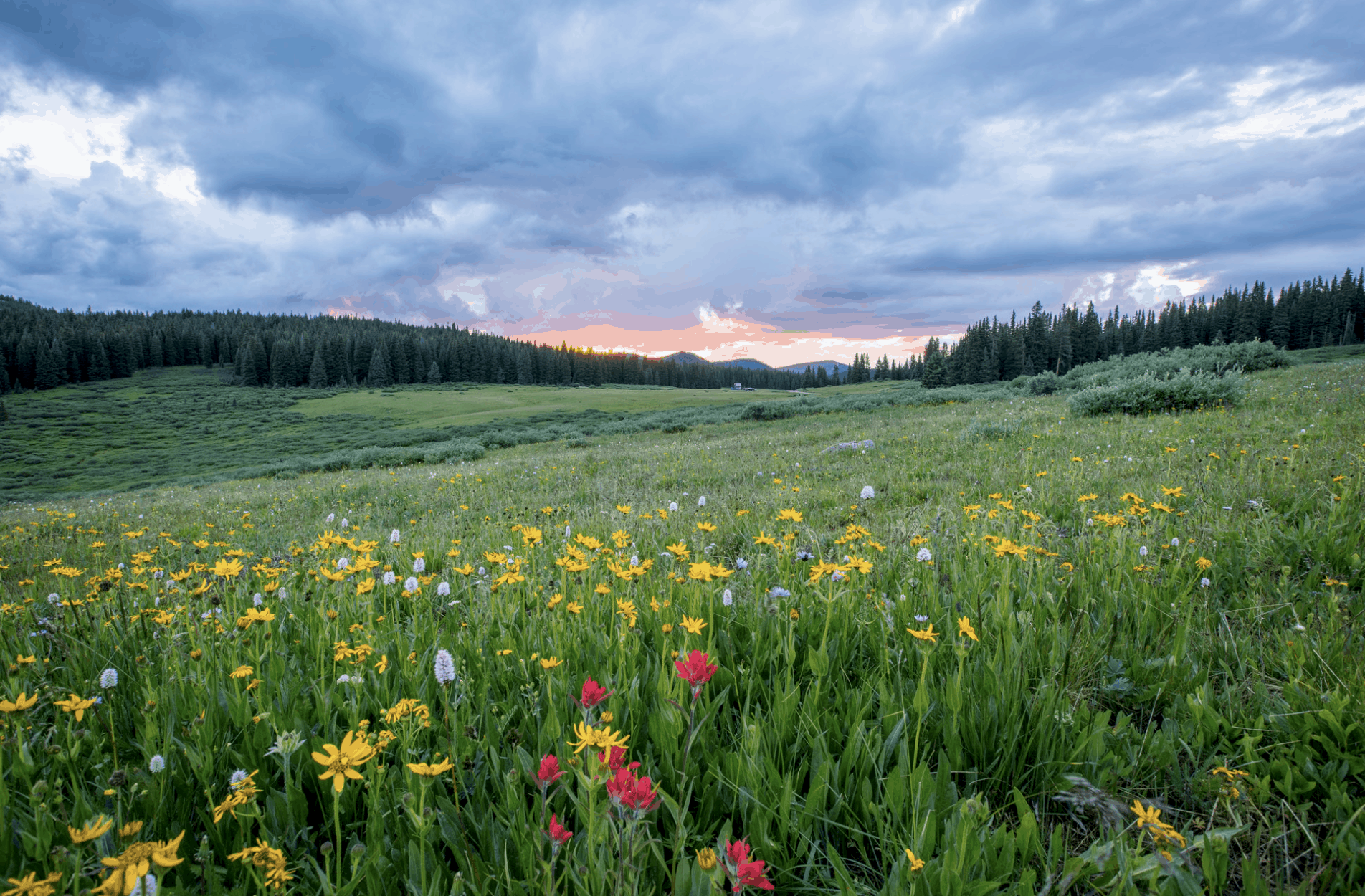

I have learned many lessons since in the 35 years that B’not Esh has been meeting, but one of the most important is that there is experience beyond language. Finding a new relationship with God is not just a matter of experimenting with new imagery that celebrates divine femaleness, but being open to new experiences. Of course, the challenge of writing about the realization that experience can transcend language is that it is impossible to put pen to paper without finding oneself back in the framework of ordinary words.

For the first time, I understood the poets and mystics who spoke of the inadequacy of language to capture the fullness of certain feelings or experiences of the divine, and I found that they evoked the power of such experiences far more eloquently than I.

There were any moments at B’not Esh that brought me to a new respect for the more-than-rational dimensions of reality. At one of our early gatherings, one of our members received a phone call in the midst of an evening session informing her that her husband had had a major stroke. She went upstairs to pack and lie down briefly before catching a plane home, and the group crowded into her room to send her healing energy. The energy was so palpable and powerful that we could practically see and touch it. She said it sustained her for the next year and she felt as if she had levitated.

We never discussed this moment afterward; whether because it was too frightening or we had no words for it, I was never clear. But we had similar experiences other times when we gathered to heal someone, when we sang together, or when we dug deeply into the wisdom of our lives to create new words of Torah.

Another time, we had a very painful discussion about abuse in Jewish families and were stunned by how many of us had been physically abused as children. The next morning at Sabbath services, the leader instructed us to go out during the silent prayer and receive a revelation! The assignment seemed absurd. How does one have a revelation on command and in the space of half an hour? Thirty minutes later, the woman who in the early years wrote much of our music, returned with the words and melody of a chant that not only became something like our anthem but that, in the time since, has found its way into Jewish liturgies in remarkably far-flung places: “As we bless the source of life, so we are blessed.”

Other times too, we were told to seek a revelation, laughed at the thought, and then returned with some extraordinary insight. Though we experimented with new images for God in the early years of B’not Esh, these experiences of the presence of God have been more important in shaping my theology than any particular language. They taught me that images are meaningful only insofar as they are rooted in genuine experiences and that it is possible for certain experiences to override and undermine language, or to provide different messages from those that language may convey.

It has taken me a long time to appreciate the full meaning of this insight in my work as a religious thinker, but, ultimately, it has led me to focus less on how we talk about God and more on where I find God in my life.

0 comments to "Moving Beyond Language"